What if you threw an area's existing bus network away and designed a fresh one from scratch? Would it improve mobility or be more trouble than it's worth? And even if it turns out not to be practical can we at least apply lessons from the design exercise?

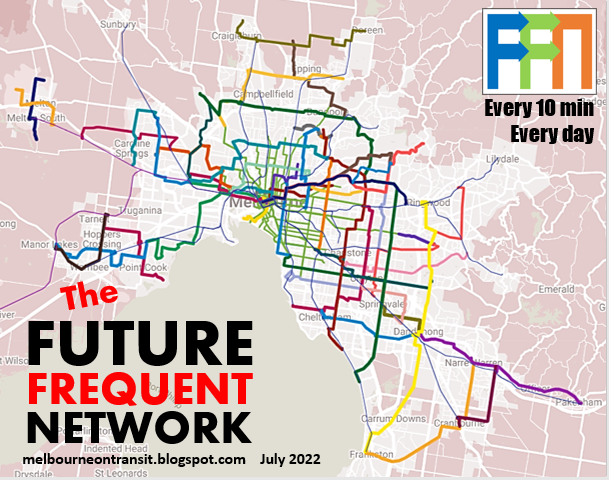

Two years ago RMIT's Steve Pemberton developed a Melbourne-wide bus network based on the 'Squaresville concept' popularised by the late Dr Paul Mees. Instead of infrequent buses winding around back streets and converging on stations and shopping centres, routes would stick strictly to the main road grid such as exists in North American cities (eg Toronto from which Dr Mees got the idea) and here in Melbourne.

Main grid routes would operate frequently so you wouldn't have to wait very long. And improved directness could make travel quicker. With a bit of walking either end Squaresville sought to replicate by public transport the anywhere to anywhere convenience of driving. Network maps could highlight the frequent routes (as they do in Toronto) to further sell the service.

Rather than having planners trying to second-guess where people wanted to go with multiple infrequent routes converging on particular destinations, Squaresville would instead have a frequent grid reasonably walkable from most places. The trade-off for this was a likely longer walk to your nearest stop and having to change buses more, even for many shorter trips (*).

I reviewed the RMIT work here. As a particularly pure version of a Squaresville network, I said it would have severe and probably fatal problems if implemented. It was even more radical than the dumped Adelaide network proposal. My alternative favoured reform rather than abolition of many existing routes and a 'modified grid Useful Network' approach that tolerated minor overlaps to serve major destinations from multiple directions.

(*) Squaresville isn't the only response to an unwillingness to presume where people want to go. Another reaction, fashionable within parts of DoT, is to avoid planning fixed routes and stops by having flexible route buses summoned by an app. Whereas Squaresville routes scale up well with good speed, directness and economy per passenger, flexible route buses tend to be less productive opposites. Can or should we have a network with both? Keep reading!

A 'world-leading clean slate' bus plan for Melbourne's west

Released earlier this week is another pure Squaresville-based bus network to chew over. Better Buses for Melbourne's West from Melbourne University promises a 'clean slate' for buses mostly west of the Maribyrnong. This includes the cities of Melton, Maribyrnong, Moonee Valley, Hobsons Bay, Brimbank and Wyndham.

Wyndham and Brimbank progressively got reformed 'clean slate' networks in 2013-7, with the former following rail upgrades. With a 2-tier network including direct main routes on a mile grid, Wyndham's current network doesn't look much different from Toronto's except for some bending to feed our wider spaced stations. The critical difference is frequency with Toronto running its main routes every 10 minutes all day all week. As for other areas, Hobsons Bay and Maribyrnong have had little bus network reform for years. Melton recently gained some new routes. Moonee Valley got some minor reform with the 469.

Reformed Wyndham and Brimbank networks sought to retain existing coverage goals (eg 90% within 400 metres of a bus) while putting savings from simpler routes towards more frequent service on main road routes. This enabled a two tier route structure of more frequent direct and less frequent neighbourhood routes. The introduction of some 7 day 20 minute off-peak frequency routes was a big step forward but service hours resources remained insufficient to boost most direct routes to run more than every 40 minutes off-peak (despite available buses as proved by widespread 20 min peak frequencies).

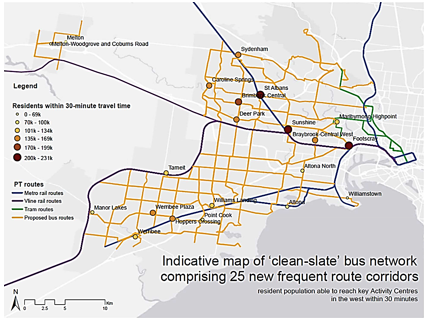

The result was that despite many straighter routes connectivity to major centres remained limited. Melbourne University researchers John Stone and Iain Lawrie found that of the west's major centres only Footscray was accessible to large numbers of people within 30 minutes by public transport. A 2018 SNAMUTS map showed a similar pattern of inaccessibility in the west, especially away from Footscray and Sunshine. This contributed to a low mode share for buses in the west (even though usage on individual buses may be strong), high car dependence and concomitant expensive road expansions unlikely to ever relieve traffic congestion.

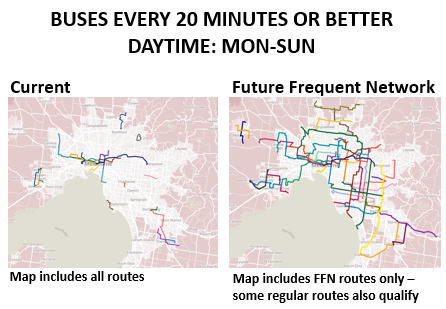

2006's Meeting our Transport Challenges proposed 900km worth of more frequent SmartBus routes. Only half were delivered, mostly in the east. That left the fast-growing west with one completed SmartBus route versus ten in the east. The effect of the SmartBus orbitals and more frequent trains in the east is clear from the SNAMUTS map above. West-east inequality was also a theme of the Rail Futures Institute Metro 2 plan I reviewed last week.

The power of frequency: Electric buses every 10 minutes

Better Buses for Melbourne's West would overturn this inequality at least with regards to on-road transport. Service levels will be high with just one service level on all routes. Frequent. More precisely every 10 minutes 7 days until 9pm dropping slightly to 12 minutes early morning and late at night. Not a single train or tram in Melbourne is as consistently good as that.

The network shake-up will see the west's 80 bus routes become 25 longer and straighter routes. Like in the RMIT plan, routes 'stick to the grid' rather than converge on major centres like Werribee, Tarneit and Watergardens (Sydenham). There is no attempt to plan by anticipated usage with almost the same route density in the Laverton North industrial area as in residential and shopping areas.

At 1500 to 2000 metres, route spacing is much wider in this network than others here or anywhere else (including Toronto). The paper says that "much of the region will be within a 750 to 1000 metre walk of stops" which many would be willing to walk if services were frequent. For 'mobility-impaired residents' there would be 'on-demand flexible route services' to provide fill-in coverage for mobility-impaired residents.

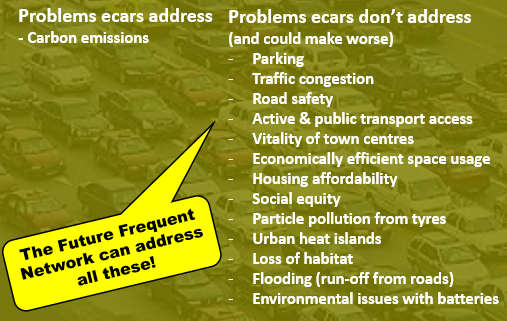

Stated benefits include savings to household budgets (as car ownership would be less necessary), higher public transport usage, equity and access to opportunity and reduced emissions (especially if combined with a transition to electric buses). Local centres might get better connectivity from a wider area but at at the cost of requiring a transfer for a lot of trips from surrounding areas that now just need one bus.

Network Evaluation was based on comparing how many people could reach major centres within 30 minutes versus the current network. That 30 minutes is based on Marchetti's Constant and Plan Melbourne objectives. It was common for there to be a doubling in a centre's 30 minute catchment with Werribee Plaza enjoying a 400% increase (see supplied diagram below).

Outer car-oriented areas enjoyed the highest gains in accessibility, with that to Hoppers Crossing increasing by ten times. Centres like Footscray and Williamstown had the lowest gains but these were still significant, particularly at nights and weekends.

The list of centres compared was from Plan Melbourne. These sorts of documents are written by white collar types who ignore the large workforce numbers in industrial areas like Laverton North or its need for any form of workforce transport access other than driving. Thus they omit it as a centre. However if Laverton North was included its accessibility would increase by maybe 30 fold given the number of frequent 'clean slate' routes crossing it compared to the sparseness of existing service.

I highlighted the need (particularly) for a Tarneit - Laverton North connection in my Job Ready Network item. This network delivers not only that but in a form many times bigger. It remains to be seen whether the buses that will run through there every 12 minutes at midnight will get sufficient usage to justify their continuation!

How much does Better Buses cost? $30 million more per year is quoted. That figure includes the flexible route bus network. There is also $25 million for 'simple intersection priority'. These figures are for the basic network. There's also an enhanced network option with a $5b works spend. More about this and the flexible route services later.

Co-ordination with infrastructure

Melbourne often does infrastructure works without simultaneously reforming bus services. For example Southland Station got no reformed bus network when it opened (or since). Level crossing removals are almost never accompanied by bus network reform even though level crossing delays might have been one reason for previous bus planners to have different routes on different sides of the track rather than faster and direct through routes. The level crossing got removed but the old bus network lives on.

The Clean Slate network punches through this inertia by often specifying through routes, enhancing cross-rail connectivity at locations like St Albans and Ginifer. In this manner connectivity to destinations like Sunshine Hospital (east of Ginifer) from the west is improved.

Something else that's special is the teaming up of buses and serious infrastructure in the 'enhanced network' version of this plan. This is something that cities like Brisbane do but Melbourne largely does not. At best buses might get some crumbs from road projects like

North-East Link whose larger effect will be to induce driving.

Better Buses rightly opens our minds as to what could be possible with bus priority and new bridges across creeks that (assuming they are kept bus only) would make some bus trips faster and more direct than car driving. Investment here would give the west connections that the east, with its more continuous road grid, has long taken for granted. Note though that there will almost certainly be political pressures from those who either don't want a bridge (especially between poorer and richer areas) or want it to carry cars too.

The basic network, designed for fast and cheap roll-out within 18 months, doesn't have near this infrastructure spend with $25 million allowed for 'simple intersection priority'. However without the new bus roads and bridges from the Enhanced Network some of its proposed routes cannot operate in their proposed form.

The authors really need to have presented a 'Stage-1' network map to show what parts of the network are possible now without these works. Even annotating the map with a black marker showing the current road gaps would have helped policy makers unfamiliar with the area. Also, because the coarser transfer-dependent network structure makes some local trips harder more should have been said about complementary walking and cycling improvements that could be an alternative for some.

Gains and costs

Summarised below. Three network options are provided. These are the existing network, a basic 'clean slate' network and an enhanced 'clean slate' network. Both 'clean slate' networks have identical service levels and catchment populations. Enhanced spends more money on capital infrastructure to speed buses and (apparently) reduce bus service hours back to where they are now.

The number of people within 800m of a frequent bus increases from 0 to nearly 700 000. This is achieved with about 25% more service hours under the basic option. Page 20 of the plan justifies this in terms of reversing the (i) decline in bus service km per capita (population grew faster than bus service km for much of the period after 2012) and (ii) historic underprovision of service in the western area.

It is not clear how these service hours are allocated, more specifically what percentage goes to run the frequent main road network and what must be spent for the demand responsive component needed to retain coverage. Though to be fair assessing the latter is difficult as it is less scalable than fixed route public transport (which is easier to cost). My guess is that the flexible route component wouldn't be insignificant given the sparseness and, in places, limited permeability of the main road network.

The increase in service hours is clawed back with the enhanced option. The secret is that the basic option is all about paring back routes and increasing frequency whereas the enhanced option adds bus priority to increase speeds (from 25 to 30 km/h) and thus bus service kilometres. That would entail spending more on fuel though electrification promises savings.

Higher bus speeds would increase the number of people within 30 minutes of a centre and bus productivity due both to the faster service and more trips a bus can run per day. The enhanced option basically spends capital to reduce operational costs, making the network more efficient. This is not a small amount, with $5 billion quoted as an approximation.

A faster and busier main network is likely to increase demand for the 'in between' flexible route services. Unlike fixed routes these do not economically scale up to increased usage. Hence more may need to be spent on them (unless they are reformed to become more efficient fixed routes). Also there is very likely to be political pressure for route changes which is likely to be in the direction of more overlaps and less economy. Thus I wouldn't be so confident about the reduction in annual bus hours spending projected, especially if increased speed promotes patronage on main routes and requires boosting service to relieve crowding (admittedly a good problem to have).

How quickly can the 'clean slate' network happen?

Better Buses claims that its plan to condense 80 existing bus routes into 25 more direct ones AND establish a complementary flexible route network could be implemented in the next term of state government. Page 21 gives a lead time of about 18 months (late 2022 to commencement in early 2024). This makes it way faster than multi-term road and rail projects.

I won't say that's not possible. But there will have to be a transformation in the way things are done. And, no that can't mean the type of change where the Department of Transport spends six months or more looking inwards while it restructures.

Current DoT processes take more than twice as long (37 months) to

start just one new bus route. That 627 example is close to the simplest scenario with one route, about 30 new stops and no changes to the underlying network that it partly overlaps.

A Clean Slate bus network transition is more complex with particular challenges in public acceptance and infrastructure. Even if it could be done in three and a bit years that brings us up to the next election which could make some pollies nervous if the network proves controversial (which, in its proposed form, definitely would).

But we cannot and should not accept existing DoT time-lines if we want every suburb in Melbourne to get bus reform at least once before most of us die. Because the current rate of change won't even guarantee that. The survival of many route and timetable hangovers from 30 or 40 years ago is proof of that.

Another case where change appeared daunting was of course the level crossing removal program. People thought it was impossible at the scale the government promised. But once there was the political will the money followed and it got done ahead of schedule by a dedicated authority. While LXRP processes were not perfect (eg in some aspects of public engagement) this project could provide a counter-example for naysayers who say that substantial bus network reform is too hard or we'd need to wait decades for it.

What's the catch?

There's lots to like about the Better Buses network, especially the turn-up-and-go frequency, simplicity and huge accessibility gains for some trips. And it's tempting to say that not only should we do this here but everywhere else.

Before rushing headlong there's things that you should know first. The writers mentioned many. They humbly (and correctly) describe the network as a 'thought experiment'. Such experiments are useful to test the possibilities of network reform at its most extreme. The theoretical improvements set a benchmark against which to compare alternative more practical networks of the type you might wish to implement.

Especially note the following:

* We'll need more train stations - quick!

The indicative network map shows many routes finishing where they meet the rail line, especially on the Geelong and Werribee lines. The only problem is there's no stations at most. Building closer stations would slow the Geelong line, making it more like a suburban service.

Not only would you need to build 7 new stations by 2024 but you'd also want some form of two tier service to add suburban capacity while preserving speed. In short some sort of

Western Rail Plan.

The

Rail Futures Institute plan I reviewed last week proposes 2026 as a date for many of these new stations to be built by. If you take that as a 'best case', and note this is a private proposal and not funded government policy, you'll be having a new network operating without half its train stations. If you want a step change in public transport usage you need to deliver a good integrated service from Day 1 (

like we did in 2015 when RRL opened), otherwise people will try it and never come back.

A more pragmatic approach is far more likely. That is to keep the current network where several routes converge on existing stations and activity centres like Tarneit and consider changes when new stations open.

* Coverage gaps cause big reliance on risky flexible routes

Better Buses reduces the number of bus routes from 80 to 25. Those that remain will be nothing like what operates now. Let's take an example from Wyndham, which along with Melton, is one of the west's fastest growing municipalities.

The 2015 Wyndham bus network (and subsequent improvements) has been so successful that most routes on

Wyndham's bus map are more productive than the average for buses in Melbourne. That applies almost equally for routes off or between the main roads. For instance Route 151 on weekdays is almost as productive as the main road route 150. And, if anything, being on smaller roads, 151 has better walking access from surrounding streets.

As a trade-off for its more frequent main road network, the 'Clean Slate' network would make Route 151 passengers either walk to Sayers or Leakes Rd. Except for Tarneit on the Leakes Rd route neither would serve the key destinations locals would most want to go to.

Figure 1 on Page 6 uses an out of date PTV map as the starting point for their network. It omits routes like 152 and 182 in the Tarneit area and 444 and 454 in the Melton / Cobblebank area. This didn't affect Tarneit much but it made their 'clean slate' network especially sparse around Melton. More people than expected will thus be beyond 1km from a bus route. In other cases they may be after a transport option that does not force a transfer.

What's meant to fill the gaps for people who can't or won't walk the distances the 'clean slate' network demands? A lot of reliance is being placed on flexible route services. This raises many more questions than answers.

First of all who can use it? That's an important question as existing buses can be used by anyone with a ticket for as many times they like. Page 21 says that the on-demand services would be for 'mobility impaired residents'. If that becomes a restriction then that disenfranchises the hundreds of thousands of people who don't count as mobility impaired. For these people we are taking away their local bus and giving nothing nearby in return.

Having pointed that out, I will now be charitable and assume that the on-demand services will be truly inclusive, ie also open to people without impairments.

There's other issues too. The operating hours of the on-demand service hasn't been specified. These are very limited with most of FlexiRides services we have recently rolled out. For instance the Rowville FlexiRide operates on weekdays only. And Rosebud's finishes very early in the afternoon. To be equivalent to the bus services removed any flexible route service should run 7 days until at least 9pm similar to the service that currently runs in Melton.

Before we leave on-demand let's look at the word 'Affordable'. There's two dimensions here; affordability for the passenger and affordability for the taxpayer. To preserve the former along with fare integration there needs to be full integration with myki. We're not told that. This is a risk because other cities have implemented flexible route services that are not integrated with their main public transport fare system.

As for the taxpayer, you want a network that delivers high patronage along with low cost per rider. That means a network that is overall productive.

Some of the local bus routes this network rips out are very productive. An example is the previously mentioned Route 151 which enjoyed 54 boardings per hour in late 2018. Maybe this has fallen since the new Route 152 started nearby but usage likely remains higher than the Melbourne bus average of 20-something boardings per hour.

Route 151 is just one productive local route that the 'clean slate' network seeks to replace with flexible services that are

inherently low productivity. Low productivity means a high operating cost per passenger trip delivered. Put in another way this means that

flexible routes do not scale up well.

You might accept the small scale if you are looking to serve a small number of passengers with special needs. Or the demographics point to thin demand. Think of a flexible route bus serving Sydney's high-income northern beaches for example.

If lots of people try to use on-demand services (very likely in a lower income, less car-owning catchment like parts of Melbourne's west) then speed and reliability drops off far faster than is the case with fixed routes. Melbourne monitors and reports on fixed route punctuality to provide a degree of public accountability. Our flexible routes, in contrast, don't have such reporting standards.

Flexible route operating costs spiral as more buses and drivers are needed to stop waiting times blowing out. Many flexible bus trials fail. In the few cases they they prove popular the best response to handle the loads is to convert them to a fixed route / fixed timetable service. High usage of existing fixed routes clearly demonstrate that areas like Wyndham and Brimbank can skip the bother and stick with fixed routes.

Getting back to public finances, governments like the assured costs of contracted fixed route bus services. They're less enthusiastic about the variable budgets of flexible routes and microtransit.

Canada's Innisfil has had to ration usage on its subsidised taxi scheme because people used it too often, something that no mass transit system should ever need to do. Other ways to limit usage include limiting service hours, accepting unreliably long wait times or requiring pre-booking. Another, and probably better option, is to just revert to having some fixed local routes inside the main road grids just as Toronto (and we) do now.

The sparseness of UoM's 'Clean Slate' network risks imposing a high dependence on flexible routes. This is especially in suburbs with high bus using demographics away from main roads. Unnecessary use flexible routes magnifies reliability risks for passengers and financial risks for government. Add the political problems associated with scrapping existing high performing fixed routes and you have a showstopper on your hands.

Some trips will be much worse than now

See the 'Clean Slate' network map (portion below) and imagine a short trip from Werribee to Manor Lakes. Right now that's easily done on the direct Route 190 up Ballan Rd. While not super-frequent it operates over long hours of the day including Sunday evenings. The 190 also serves Eagle Stadium, Werribee's main sporting complex.

Even though Ballan Rd is a main road, the 'Clean Slate' network will have no bus along there. Going off the map a Werribee - Manor Lakes trip will require a bus to bus transfer including having to cross roads at a particularly hostile intersection (Tarneit / Heaths Rd).

What if it was raining or very hot and you wanted to change at somewhere more 'civilised' eg a train station. A longer option involves a train to Tarneit West (if that ever gets built) and a bus to Werribee, traversing many more kilometres than today's direct bus. And Geelong trains are as infrequent as every 40 minutes on weekends meaning that even this short trip could take an hour. A similar issue applies in Melton where weekend gaps between trains are more like hourly.

The conceptual network is based on 'no improvements to rail service frequencies' but it is acknowledged that these will be beneficial for the network with more efficient connections possible. This entails Metro and at least the Geelong line to Manor Lakes running every 10 minutes or better seven days.

Even after train improvements you'll remain with a network that in exchange for making trips to destinations people commonly go to harder makes travel to places people rarely go to easier. Some will benefit from better cross-regional accessibility but a lot won't. Many passengers would prefer a reasonably direct single seat bus coming (say) every 20 minutes over catching two buses with 10 minute frequencies with inconvenient road crossings to change. Ballan Road's route already enjoys that level of service all day but it's possible to extend it to more routes by working the existing bus fleet harder.

Considerations like these should determine the priorities for bus network upgrades for campaigns such as Sustainable Cities

Better Buses for Melbourne's West (same name as the UoM paper) and other political advocacy as we may see in the lead-up to the state election.

Usage will vary greatly between routes

The network map shows corridors not routes. It really needs to show routes to be a serious proposal. But I'm going to assume a 'strict Squaresville', ie every route is pretty much a straight line. This optimises access where destinations are evenly distributed and centres don't exist. It also maximises the frequency possible as there are almost no overlaps.

In the 'real world' there are centres like Werribee Plaza and Woodgrove Melton. Some stations are busier than others. And transfer penalties do exist.

Middle Toronto suburbs with east-west buses serving high-rises along the subway are a world away from industrial Laverton North through which the Clean Slate network seeks to run buses every 12 minutes until midnight. Less dramatically you have roads like Sayers Rd running east-west through Wyndham. That has lots of housing but the route's western terminus (currently no station) and eastern terminus (Aircraft Station with the route cutting through the RAAF base) are both extremely weak. This is in contrast to the existing networks in Wyndham and Brimbank were almost all routes have strong anchors at both ends (think Werribee, Tarneit, Sunshine, Watergardens etc).

Even assuming the network operates as planned with lots of people willing to change buses some routes will be much busier than others. Thus there will be pressures to adjust service levels and/or extend routes that finish just short of a major centre to it. That could undermine the network effect that Squaresville relies on. You are better off applying a modicum of planning nouse and design useful routes that are not set up to fail.

If you don't do this network atrophy can be a problem. A network might start off simple and frequent but later atrophy into complexity (historic examples

here and

here). The existing Wyndham and Point Cook networks have held up well with subsequent changes and additions improving it.

But where two routes try to run a more frequent corridor, as is the case in parts of Brimbank (eg 400/427 or 426/456) then atrophy can set in as other considerations take priority over coordination and even frequencies. Brimbank's network clarity also suffered when the 422, overlapping other routes, was introduced. A better use for the resources would have been better frequency and operating hours on routes like 423, 424 or 425.

My guess is that the UoM suggested network won't necessarily be very robust since the demands for people to have their buses back will be overwhelming. Especially where the case to remove them didn't exist in the first place due to reasonable directness and good usage. Further work to refine the network modelling could include the above map showing rough passenger numbers on each network segment (presented by colour).

Big roadworks will be required

The basic clean slate network is about reformed routes and vastly better frequencies. The enhanced version speeds it up with bus priority. That requires major works and capital costs for the needed bus lanes etc.

In case you're wondering, not all the roads on the network map exist. For instance there's currently no direct road connection from Altona Meadows to Sanctuary Lakes. Similarly Burnside lacks connections from Deer Park and Albanvale. Creeks, freeways, historic urban growth boundaries or council areas are all reasons for limited permeability.

Building these links as bus/bike/pedestrian ways could be less objectionable to residents in local streets and make public and active transport faster than driving for some trips. But I would still expect political pressure, either against any link or wanting it for cars too.

Evenso it would be wonderful if links like these could be built. They could give some large mobility gains. As an example the trip from Burnside to Sunshine Hospital would currently involve a bus and a train taking over 50 minutes. Completion of a bus road and a direct route would more than halve travel time to 20 minutes. In some cases walks to schools could become easier too.

The 'Clean Slate' approach delivers the biggest gains sooner by rolling out the basic network with an option for enhancements later. These can be staged if required. However even if the fastest bus speeds aren't achieved on Day 1, one thing is super critical. That is pedestrian access to and between buses. If that's not sorted out then the new network, so heavily reliant on transfers, will not work.

Let's look at the Tarneit/Heaths Rd location we needed to change buses at to do the Manor Lakes - Werribee trip discussed before. That trip requires a change from the red route to the blue route. It's a walk of about 200 metres. This is because, unlike older tram stops in inner suburbs, bus stops are not at their most convenient and accessible point - right at intersections. This setback may be due to wider roads, inconveniently placed driveways and large turning radii loved by car throughput-loving traffic engineers.

Note that the intersection has a roundabout instead of signals. Roundabouts give cars absolute right of way with continuous traffic flow preventing safe and reliable pedestrian access. This affects (i) access to direct routes like in the 'Clean Slate' network and (ii) connectivity between intersecting routes that the 'Clean Slate' network heavily relies on.

Local walkability and bus access would improve if there was an LXRP style

roundabout removal program to signalise large intersections. Signals would also need to be tied to appropriate bus priority.

I would even go so far to say that even a basic 'Clean Slate' bus network cannot reasonably proceed without (i) all roundabouts on its routes (particularly at transfer points) being replaced with signals and (ii) easy and responsive pedestrian crossings at every stop (as people have already walked long enough without having to wait or divert further).

While both are also beneficial for active transport and should be done, requiring them on Day 1 would affect the new network's roll-out speed. Unless money can be found in the roads budget the $25 million allocated won't be enough since it will barely fund three roundabout removals. I'd have liked more detail in Better Buses about this potentially significant constraint.

Winning political acceptance

Better Buses correctly identifies this as a problem, even exceeding the ability to raise the $5 billion for capital works. The enhanced network option (in particular) relies on substantial road space reallocation to speed buses. About 10 years ago bus lanes were removed from Stud Rd in the east due to motorist opposition. The main bus using those lanes was the 901 SmartBus which runs every 15 minutes (even in peak). Thus the lane appeared empty most of the time. The Liberals removed the lanes. Labor hasn't brought them back.

The one route per road philosophy of Squaresville along with services every 10 minutes invites similar issues in the west. Unless it's a separate busway cut off from cars buses will need to be seen to be operating at much closer intervals than 10 minutes, carry more passengers and (maybe) have electronic 'passengers on board' signs on the back to demonstrate the traffic relieving powers of buses and thus their value even to non-users.

Local walking and cycling improvements (which can also aid access to bus stops) may have a greater chance of success, especially if there is a bottom-up community engagement process and good active transport budgets. Along with less overtly noticeable bus priority measures at the main delay points.

More could also be done to build new suburbs around fast bus and active transport only corridors operating through their centres. When people move house they make many changes in their lives including transport modes. Good suburb design backed up by service can make public and active transport use the natural choice for trips these are convenient for.

Another dimension with public acceptance is the bus users themselves. Those who participate in surveys or attend in-person sessions may not necessarily be representative of riders. But they can make a lot of noise and potentially stop a network change.

The new networks that were implemented in Wyndham and Brimbank survived a process that included public consultation. So (largely) did those in Auckland and Sydney. But Transdev's network greenfields, planned at the same time as Wyndham's but with inferior public engagement, did not. This network is vastly more radical than Auckland's and may well

suffer the same fate as Adelaide's.

While the 10 minute network has benefits regarding connectivity across say a 5 to 20 km distance, it risks making a lot of shorter distance and more frequently made trips worse. Public saleability is likely to be worse in areas where the network is already half good.

For instance Wyndham and Brimbank's networks are reasonably direct and lack the horrors of networks in other parts of Melbourne (eg no Sunday service, reduced summer timetables, confusing deviations, dead end termini, indirect loops, etc). There are still issues with coverage, limited operating hours and lower and desirable frequencies but these can largely be addressed by improving or extending the current network.

It is quite reasonable for a person on a popular route that's being taken away to ask 'Why?' It won't be easy to give a good answer, especially if the replacement is an inherently cost inefficient flexible route bus.

A more practical network alternative for testing?

We have been given details about three bus networks in Melbourne's west. The current, the basic 'clean slate' version and the faster enhanced 'clean slate' version. The last two have some big improvements compared to the status quo for certain types of medium distance trip that are currently mostly made by car.

Major issues with the last two include the dependence on changing buses, the removal of popular routes and uncertainty over the cost of the demand responsive portion of the network (or even whether anyone will be able to use it). Even widespread 10 minute frequencies may not be a sufficient to win wide support.

The UoM team made it hard for themselves because over half of the network they used (Brimbank and Wyndham) had their worst problems removed through recent network revamps. Other parts eg Maribyrnong have problems but also a lot of fairly frequent routes. If the researchers chose other areas, notably Mulgrave/ Springvale/ Dandenong, Hampton Park/ Narre Warren or Epping/ Reservoir/ Heidelberg/ Eltham they would have been able to find more justifications for reform as aspects of their networks are truly horrid.

Notwithstanding the area choice made, it would have been interesting to have included an equivalent cost more practically-based middle-ground option as a comparison. That could include: (a) the acceptance of some route overlaps where this retains connectivity to major centres and stations and (b) the retention of midblock 'coverage routes' in place of the proposed flexible services.

Extra route kilometres on the main network could mean that fewer routes operate every 10 minutes / 7 days. On the other hand savings could be got from (a) not running buses every 12 minutes at midnight through industrial areas and (b) avoiding high per-passenger cost flexible services.

Funding like the suggested $30 million per year would deliver a lot of gains. Most of which would be frequency and operating hours increases on existing main road routes (including boosts to every 10 or 20 minutes). Being largely timetable changes (at least in already reformed areas like Brimbank and Wyndham) implementation will be fast and uncontroversial.

This option would be vastly less disruptive and more saleable than the pure Squaresville options tested. However its theoretical network benefits may be less. How much less and what would be the opportunity costs? This is something that research including this as an option could have established. Such a review of a practical option would have added real-world value to the research for a wider audience including state government, local councils and community advocates.

Conclusion

Melbourne University has produced a 'thought experiment' grid bus network for Melbourne's west. It shows that, subject to trade-offs in coverage and transfers, a reformed bus network can multiply peoples' access to jobs, education and opportunities. Its 25 streamlined routes puts nearly 700 000 people within 800 metres of day and night frequent public transport. So many Melburnians haven't had that level of service since

tram timetables got cut in the early 1950s.

The enhanced option proposes something we too rarely do with buses in Melbourne; that is regard them as faster high order transport with their own priority, exclusive bridges and serious capital investment. The $5 billion suggested is less than a major road or rail project but would deliver accessibility benefits over a wider area. While the comparison isn't drawn, this enhanced network could be as significant for the west as the Suburban Rail Loop will be for the east.

With such huge benefits, can I recommend this precise network?

No!

Could it inspire the development of more suitable bus networks?

Yes!

As a rigidly applied Squaresville, this network creates too many have nots living between often poorly permeable mile blocks. Changing, that this network forces even for local trips, will be a miserable experience waiting for gaps between cars at treacherous roundabouts and walking along back fences to stops. Riders will lose their local bus despite it being well-used while numerous routes will traverse industrial areas every 12 minutes at midnight. And users must toss up between longer walks or chancing it with indirect, uncosted and possibly limited hours flexible buses. The political and financial uncertainty of this network form such a counterweight to its promises that could prove its undoing.

What could be a better alternative if you had (say) $30 million per year for improved bus services in an area like Melbourne's west? Especially if you were approaching an election and didn't want to be too controversial?

For western areas, like Brimbank and Wyndham, with recently reformed good performing networks serving favourable catchment demographics, you're best off throwing more buses on existing routes that already form an effective grid. Instead of running every 20 or 40 minutes the grid routes would be every 10 or 20 minutes with longer hours. Potentially 24 hours on weekends in some cases.

Top performing bus routes worth upgrading are

listed here (with many in Melbourne's west). And for more background on Wyndham

see here. Local roadworks would also progressively improve pedestrian access and connections to and between stops on main roads to encourage usage. Add bus electrification, train frequency upgrades and cycling infrastructure for a broader cost of living and sustainability narrative.

Other areas really do need bus network reform of the type Brimbank and Wyndham have had. Before an election I wouldn't get too much stuck in to the detail. I'd certainly not be publishing maps showing lots of popular bus routes vanishing. Key needs in areas like Greater Dandenong include longer operating hours and weekend service, even if these are added to existing popular routes now pending a wider reform to simplify the network later. A (non-exhaustive) list of routes that could do with Sunday service is

here. Again a wider view would be beneficial, eg a plan to deliver 7 day service on all metropolitan residential area bus routes. The cost of upgrading the most needed routes wouldn't be high - somewhere in the low millions per year. There are even cases where 10 minute service could be economically rolled out with

minor reforms involving a few routes only.

The end point of these approaches would be the same - a simplified network with more direct routes, better frequencies and longer operating hours. But, unlike the UoM's version of Squaresville a '

modified grid' approach would have fewer transfer penalties and wouldn't be taking an axe to coverage. This makes it much more like the actual network in Toronto that Dr Mees got his Squaresville inspiration from. Implemented networks in Auckland, Sydney, Perth and

Brampton (outside Toronto) are other working network reform templates.

Buses can be fast, frequent and direct but are too rarely thought of and delivered as such in Melbourne. Dr John Stone and PhD candidate Ian Lawrie have helped shift the discussion agenda for bus services in this helpful direction. That's a valuable service given the untapped opportunities, relative affordability yet past recent political wariness when it comes to bus service reform in Melbourne.

The time for ambivalence is over with Better Buses for Melbourne's West telling us in no uncertain terms the benefits of acting now on buses.

Comments are appreciated and can be left below.