Public transport infrastructure is worthless without adequate services to run on it. One should not get too far out of kilter with the other, otherwise either infrastructure utilisation or reliability will suffer. This should go without saying but hasn't in recent times.

The 'service first' remit of

Melbourne on Transit requires me to be particularly sensitive to cases where (a) transit service lags infrastructure and (b) inadequate infrastructure seriously impedes frequent, reliable and connected services. This is a different emphasis to that of the current government whose 'infrastructure first' approach in Melbourne has consistently favoured infrastructure builds unbacked by service (as will later be demonstrated).

Spiralling construction costs and budget-crippling interest payments could mean that the current government's borrow and build infrastructure agenda takes a breather. 2018 represented the high point when anything was possible, even

trams to Rowville. The

2023 state budget started pruning and added little new. Expectations are even lower for this year's budget.

Changing post-pandemic travel patterns that flattened the peaks have made providing 'all day frequent service' a higher immediate network priority than peak capacity on most corridors. And community needs for such service are rising. For example largely migrant-driven population growth in unserved estates has rebounded, housing is under pressure and

weekend Metro and V/Line patronage is booming. All this is putting pressure on various government services, not just transport.

Campaigns, notably in Melbourne's

north and

west, are calling out inadequate train and bus services relative both to Sydney and more politically advantaged parts of Melbourne.

So little has been achieved in the 1000 days since Victoria's Bus Plan came out that it can now fairly be called a flop after many meekly suspended judgment for so long.

This is not the first time the "20 000 new bus services" figure was used. On 24 October 2023, soon after gaining the portfolio, the minister told the Metropolitan Transport Forum that the government had added "20 000 new bus services in 9 years".

This way of presenting achievements (by adding up numbers since you came to office) is exactly how you'd do it with capital projects like schools, hospitals and level crossing removals. Or job positions like teachers, police and nurses.

Transport service additions is different. The number needs to be qualified on a per day or per week basis. Per week gives the bigger number so politicians tend to like it, as with this 2021 example for metropolitan trains. However it is also defensible because different days may get different numbers of trips added.

Without qualification the claimed achievement becomes much less impressive. A single bus route with 8 trips per day is all that is needed to exceed the quoted '20 000 new bus services' (since 2014). That's a low bar and certainly incorrect. Yes, those unfamiliar with describing transport services can just as easily understate as overstate achievements.

So how has public transport service really fared since 2014? To find out we need to delve deeper which is what I will do here.

Counting trips - not always the right way

If you're talking about service upgrades on just one simple train, tram or bus line, it is reasonable to say number of trips. It's clear and people can see those extra entries in the timetable.

Unfortunately, simply counting trips is a poor representation of service increase when applied across a network. This is because some routes are vastly longer than others. Adding a short university shuttle route (as the government has done several times) adds hundreds of trips per week. Whereas upgrading weekend frequency on (say) a long orbital SmartBus might require far fewer trips but cost much more. Similar applies when comparing metropolitan and regional train service additions.

Service hours or kilometres operated per year are better measures of service resourcing that cancel out variations attributable to different route lengths. Budget papers use the latter so I will too.

Just like one corrects for inflation when comparing peoples' wages over the years, one should account for population when comparing service trends. Especially in a rapidly growing city like Melbourne. With both annual public transport service kilometres and metropolitan population figures easy to get this gives a service per capita value that can reasonably be compared over time.

Previous service per capita measurements

Professor Graham Currie from Monash's Public Transport Research Group kept service per capita statistics for Melbourne up to 2019. Additional context appears in this 2014 engineers presentation.

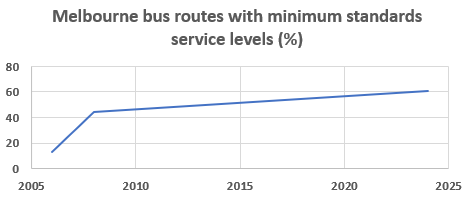

From about 2005 service grew across all modes in absolute terms. Metropolitan bus rose the fastest thanks to the 'Meeting our Transport Challenges' minimum service bus upgrades I recently discussed. Metropolitan rail was slow to grow but eventually took off on some lines, lagging the patronage boom by about three or four years (political context here). Tram usage also grew strongly but service hardly responded.

There was a significant fall for bus around 2012. The 2014-15 Budget Paper 3, p247 attributes this to less dead running as part of the new metropolitan bus franchise. If so this should possibly not be counted as service. Thus I suggest caution in interpreting data around then including in the tables that follow. Especially as metropolitan bus greatly influences the total result.

Absolute growth for all modes, especially train and bus, resumed the following year, albeit at a slower rate. But Melbourne's fast population growth exceeded service growth after 2012, with service per capita peaking in 2012 at just over 37 km per person per year across all modes. From then it steadily fell to about 33.4 km per person per year in 2017-18.

An updated version of the service per capita graph from Prof Currie had service per capita falling further to 32.7 km in 2018-19. This means that while it has added some public transport service, the Andrews government failed to arrest the per capita decline in its first term. In other words Melburnians had less service per capita in 2018 than they did in 2014. It is possible for the median Melburnian to have got more service but if more people were in growth areas with no or sparse service then mean service per capita could still decline.

The cessation of this record series in 2019 has meant that we don't know service per capita during the pandemic and afterwards. There may even have been rises in the year or so population growth was lower. Election year 2018 was when its willingness to promise major infrastructure (including the Western Rail Plan, Rowville Tram and Suburban Rail Loop) peaked, while a few years previously, in 2015, was when state government interest in service reform started to cool.

Since the minister was referring to their record since 2014 I want to go back further if possible. This is desirable because V/Line has emerged as a major rail carrier in suburban Melbourne and it would be worth seeing changes in its service levels.

The budget papers

The state budget papers (No 3: Service Delivery) give aggregate service levels by public transport mode. This is in the form of million kilometres per financial year scheduled. Links to them here:

2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 2023-24

Budget Paper 3 information with regards to public transport service across the state (excluding school buses) is extracted below:

All numbers are actual except for 2022-23 (expected) and 2023-24 (target). Metro total excludes Regional train/coach (i.e. V/Line) and Regional town bus. Notable data variations are said in the BP3 footnotes to be due to category changes for regional buses and coaches (2007 and 2008) and reduced dead running for Metropolitan Bus Franchise routes in 2012. The latter may mean that the indicated reduction in service may be less than appears.

V/Line trains and coaches have had the biggest service growth. Annual kilometres operated more than doubled in 20 years, aided by infrastructure (RFR, RRL) that, unlike level crossing removals, had a large service component. Metropolitan bus, the main and often only public transport in growth area neighbourhoods, was most notable for its high service growth between 2005 and 2010.

Regional bus service kilometres is up by over 50% due to regional city network upgrades. In fourth spot is metropolitan trains. The main driver of service growth here has been electrification extensions in the north and frequency boosts in the east. Slowest growing are metropolitan trams. The stagnant mode in Melbourne's network, they have enjoyed few gains in network extent and frequency despite catchment densification and population growth.

The graph below summarises the above, showing service growth by mode relative to 2002. As for interpretation, if a line is at 1.5 this means that there's 1.5 times (ie 50% more) the service kilometres for that mode since 2002.

Service per capita trends since 2002

So far we've discussed absolute service levels. Even if annual service kilometres are maintained or even growing (which they have been) access to them may still be declining if the settled area is increasing (which it is). This is why service per capita is a good measure, especially for a city as fast growing as Melbourne is.

The table below is the result of dividing annual service operated by June 30 population (ABS

metropolitan or

state figures depending on mode). For some reason the metropolitan totals are slightly higher than Prof Currie's but the trends are the same.

Like Prof Currie I excluded V/Line from the metropolitan total, though it needs to be understood that in 2022-23

about 40% of its non-Southern Cross station boardings are now at metropolitan stations like Tarneit, Wyndham Vale, Melton and Deer Park. Not only that but the busier V/Line stations

now get more boardings than most Metro stations who nevertheless enjoy between two and six times the daytime frequency, especially on weekends.

In broad terms metropolitan service per capita rose and then fell while statewide service per capita largely held up, effectively preserving the 2000s gains. This is because (a) metropolitan Melbourne's population has grown faster than the state average and (b) the two regional service types grew faster than most metropolitan modes. Thus metropolitan service per capita is now very close to that for the state as a whole. Note that the 2021 per capita rise across Melbourne modes is a blip caused by the pandemic-related population loss (which was later reversed).

The eagle-eyed will note that while metropolitan total per capita is just the sum of service km per capita on the three metropolitan modes, you can't simply add per capita service for all the modes for the Victorian total. This is because I'm using different populations based on who these modes predominantly serve. While not perfect, I've used metropolitan population for the three metropolitan modes, state population for V/Line and the population outside Melbourne (ie state - metropolitan) for Regional Bus. Adding per capita service of different modes also effectively gives different modes equal weighting when this is not so in relation to factors like catchment populations, network benefits, operating costs etc. Thus I'm reluctant to do it.

Percentage change in service per capita

Specific service initiatives (or their lack) become more visible when you tabulate percentage change in service per capita by mode by year. Red is decline, orange is a small increase (up to 1%) while green is a larger increase.

Note: Growth to 2023 not included as 2023-24 numbers are targets only. 2021 Melbourne increases due to the pandemic-related metropolitan population decline.

It's easy to spot the times when governments were serious about service; just follow the green squares. In order of time these include regional city bus boosts (2005), regional train and coach (mostly Regional Fast Rail associated), metropolitan bus (MOTC program) and metropolitan train (driven by surging patronage 3-4 years prior). Priority then returned to regional train and coach due to the Regional Rail Link and Ballarat line upgrade projects a few years later. 2021's green squares are largely population related so should be ignored except for metropolitan bus which did see some real service growth.

The graph below gives a wider long term view. V/Line is the big winner, with successive rounds of service upgrades that have enabled it to hold its position. Similar could be said, on a smaller scale, for regional buses. Also assisting the regional modes per capita performance is slower non-metropolitan population growth.

Trams, despite densification in their catchments, have been neglected by successive governments, with 24% less service per capita than in 2002. Metro trains, the backbone of the network have remained stagnant per capita long term. Metropolitan buses enjoyed gains in the first 10 years but have levelled out if not fallen per capita since.

How has the current government performed on service?

With both absolute and per capita service information available, we can now discuss the government's record on service. As you can see below there are large differences between modes.

The first point is there has been growth in the absolute level of service across all modes. When a minister speaks this is likely what they will point out. The second point is that the two heaviest used metropolitan modes (Metro train and metro tram) which account for maybe two-thirds of the state's transit usage, run fewer services per capita than they did in 2014.Its reluctance to add service in a growing city means that the current state government is presided over a service level recession on the public transport modes Melburnians most often use. If one justification for this was equity, for instance by prioritising bus services in high needs areas, then this doesn't hold water given the failure of Victoria's 1000 day old Bus Plan.

Metropolitan buses may have just held their own on a service per capita basis, although even that is debatable giving lengthening multi-decade service backlogs in areas like Knox and the absence of any service growth in expanding areas like Pakenham, Officer, Mambourin and Mt Atkinson. A Metro Tunnel-associated timetable may boost service on some train lines but prospects for trams, in a city that professes to love them, remain distant.The third point is that the lower patronage regional modes have done much better, with per capita service holding up. V/Line, for example, has had significant investment in service every few years since the early 2000s. Regional city buses have also had significant gains, though much of their higher per capita growth can be attributed to lower population growth outside Melbourne. Like with the growth area bus examples above, there is again a need for qualifications, eg the fast-growing Melton corridor remaining with an hourly weekend frequency for too long. Strong population growth, the low overall quantity of annual service kilometre increases and their deployment on modes with the fewest passengers may explain why governments and passengers may have differing views on public transport services and the extent of improvements made.

The main caveat in all this is data quality, especially for the last few years. This is for both service (2021-22 being the last actual data) and population (due to the decline and then the rapid Melbourne rebound). The release of another year's of service data in the May budget and population from ABS later this month will help clean much of this up.

How far is infrastructure ahead of service?

There is no doubt that Melbourne's trains and buses are what a private business would call 'lazy assets'. That is they sit idle for many hours of the week when they could be in revenue service (and attract reasonable patronage).

The graph below compared trains per hour frequency of three major Melbourne lines of roughly comparable length across most times of days. All lines operate a frequent peak service with at least 8 trains per hour average arriving at Flinders St between 7:00 and 8:59am. Not all trains serve all stations but gaps are not serious. In contrast Craigieburn and Mernda lines operate at only half Frankston's frequencies at most off-peak times. This is despite potential to be much more frequent as demonstrated by the intensive peak service that operates.

In more passenger friendly terms 6 trains per hour is service every 10 minutes, 3 trains per hour every 20 minutes, 2 trains per hour every 30 minutes and 1.5 trains per hour an embarrassing every 40 minutes.

Below I take the am peak trains per hour and assign them as 100%. Then I compare off-peak trains per hour for each line and compare them with peak frequency. The Frankston line, with its 5 minute peak/10 minute off-peak service, holds up better in all time slots. Meanwhile service collapses on the busy Craigieburn and Mernda lines to between 18 and 38% of peak service. This is despite catchment demographics that lend themselves to high all-day usage and higher observed loadings on the off-peak services that do run relative to the Frankston line.

This exercise shows that public transport service badly lags available infrastructure, with the difference often greatest on lines with high social needs that have reliably voted Labor. While I covered trains the same applies to buses, especially on weekends, as

I discussed here. The numbers demonstrate that the current government has let service stagnate with the result that it now has a lot of underutilised assets that the community is not getting full value from.

What if the Andrews-Allan government had built a little less and used the money saved to retain service per capita at the level it inherited? What sort of gains would have been possible?

For Metro Trains that would have meant we'd have retained 5.0 km of service per capita rather than the current 4.8km. That's 4% more. Add that to the current 24.9 for about 1 million more service km per year or 20 000 per week.

If applied to ten 40km long lines that's 50 extra trips per week or 7 trips per day. That should be enough to cut maximum waits from 30-40 to 20 minutes across almost the whole network between 6am and almost 10pm all week. This would be a major advance for the small increment in service needed.

And it would set the scene for a staged roll-out of the minister's much mentioned but little progressed turn-up-and-go 10 minute frequencies, with a Ringwood upgrade being especially cheap (with marginal seat benefits too). Right now all eyes are on seeing whether the proposed timetables associated with the Metro Tunnel reverses the per capita suburban rail service drop, and whether all lines stand to gain or just a few.

Retaining 2014's per capita service would have benefited trams even more. And they deserve it due to their catchments densifying. By now we'd likely have eliminated 30 minute Sunday waits and got evenings from every 20-30 to every 15 minutes all week on a lot of routes. Which is progress towards a 10 minute service (especially since so many are almost there at every 12 minutes).

Buses sit at about their 2014 per capita service. But if you consider that buses were underserved in 2014 and populations in outer areas have grown faster than the metropolitan average one should (along with suburban V/Line) use more nuanced population samples to reflect local growth and needs. If this was done Pakenham and Melton would stand out as two areas with large per capita drops in service.

Conclusion

More trips run on our public transport than they did in 2014. However service levels on the busiest metropolitan modes have lagged population growth. The result is a per capita service recession on the busiest metropolitan modes that leaves thousands more people underserved each month.

Millions more would have had access to better public transport services had the government just retained service per capita at 2014 levels. But they didn't for metropolitan train and tram while being sluggish on buses.

Will the ministers and government now act, even if they might need to slow (now arguably less urgent) infrastructure builds to fund it?