20 years ago the late Paul Mees described a public transport network topology he called Squaresville in his book A Very Public Solution. It was a grid of direct and frequent linear routes along the main road grid common in North American cities and others like Melbourne (and the American-inspired Mildura). Everyone would be within walking distance of one north-south route and one east-west route and, with zero or one connection, be able to access all areas.

Squaresville particularly appeals for diverse journeys in a dispersed, weak-centred city. These are precisely the type of trips that current radial networks are poor at. The concept of one route per road has potential benefits including simpler, more direct and more frequent routes. However such a network would radically change travel for most existing passengers, and not always for the better.

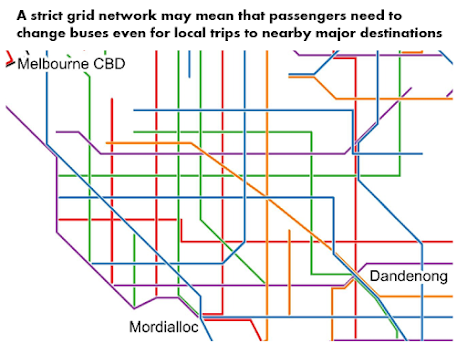

The main shortcoming is the increased need to change, especially for some local trips currently possible on the one bus. You could partly mitigate that by making changing easy. That means turn-up-and-go service on all routes to minimise waiting and stops at intersections to cut walking. Even where our busiest routes cross we don't currently do this well as exemplified below.

What would a Squaresville-type network look like in Melbourne? And how frequent could it run with existing bus service hours? The boffins at RMIT (Mees' almer mater) have answered these and more questions in a recent study. If you're an academic with access you can read the full paper by Steve Pemberton here. It even made it to commercial TV with this Ch 9 news report.

RMIT found that if you tear up the existing bus network and run frequent service on 'mile grid' main roads you can deliver faster trips than the current network. The biggest gains would be in the outer municipalities like Wyndham, Casey, Yarra Ranges, Maroondah and Melton, which currently have few if any frequent bus routes.

The maps below show how much more frequent service there would be. Instead of being limited to about 20 routes (half of them SmartBus, the other half inherited from Met Bus) it would be now on 96 routes more widely spread across middle and outer Melbourne. Frequent service is defined as every 12 minutes peak and 15 minutes interpeak. This service level was based on what could be done by reallocating existing service kilometres. That compares favourably with the 20 to 40 minute frequency on most existing routes.

It sounds good but where's the catch? There's several. Probably enough to sink it in the real world. Eg:

1. Hundreds if not thousands of stops ripped out; longer walks for many people. Instead of routes designed to place residents within 400 metres of a stop (an existing guideline for planning) the new network will be coarser with distances extended to 800 metres. Possibly more in suburbs with indirect street layouts and difficult to cross main roads. Walking further to a more frequent service will indeed save time for many people. However statistical averages are cold comfort, especially for the less mobile who may lose their bus.

2. More changing buses, even for short trips to major destinations. Below is an extract of the network in the south-eastern suburbs. Dandenong and Ringwood look like gaining with frequent service from many directions as befits their status. However busier places like Box Hill, Chadstone and Monash Clayton don't get much. Indeed they receive fewer buses than much quieter Mordialloc.

5. Walking and waiting costs not fully counted. Everyone wants a frequent service to their door. But the public transport network is not a private taxi. We grin and bear walking and transferring in exchange for a cheap and frequent service. However when testing network options you do need to compare transfer penalties since waiting an unknown time on a miserable day is undoubtedly worse than a route taking you right there. A trip involving a random arrival to a bus every 15 minutes and then another change can potentially involve 30 minutes waiting, making the total travel time highly variable. And that assumes everything is on time. These inconveniences are real and it's silly not to factor them in, especially when comparing network types. When this variability is considered some claimed time saving benefits will vanish or be hardly worth it. Again reliance on averages can underestimate costs.

6. Reliance on failed or unproven 'flexible route' or 'autonomous vehicle' technology to make network coverage acceptable. They are flogging a dead horse here. The less someone knows about bus planning the more likely they are to fall for so-called demand-responsive transport as a widespread solution to the 'last mile' problem.

It is true that an infrequent local bus around the back streets is unappealing to those with other transport options. Nevertheless it's usually better than other things sometimes suggested. Flexible route services are only flexible on the provider's terms and not the customer's. For example systems can require long periods of notice (1 to 24 hours) to be given before riding. Frequency and operating hours can be poor. And their reliability is lessened by having to deviate near other peoples houses. Flexible route buses have been tried since the 1970s with most attempts failing. Their low productivity means very high costs or very poor service. Mostly they are a false hope for reasons explained here.

Then there are autonomous vehicles. These are great in closed systems isolated from all other traffic. For instance driverless Metro systems where an all-day frequent service can run with reduced labour costs. However in open traffic environments like residential streets they are not practical. Especially when we want something that is known to work now to fix today's bus network issues.

7. Base frequency determined by existing resources rather than connectivity with trains. A 15 minute base frequency matches what we have for SmartBuses on weekdays but does not match our trains (which are moving to a 10/20 minute base service). The result of this would be a system that inherently does not harmonise for all trips. As an example a 10 minute train intersecting with a 15 minute bus provides good connections that recur only every 30 minutes. This is poor from the point of view of having to juggle departure times. It's even worse with 20 minute trains where the best connections recur only hourly. The way around this is either to have buses every 10 minutes (extra cost) or a mixed network where the busier routes are every 10 minutes while the quieter ones are every 20 minutes. While the latter represents reduced frequency it does mean that the best connections recur only every 20 minutes, ie better than up to 60 minutes before.

Other network options

Notwithstanding issues if implemented the RMIT work usefully establishes a baseline for one type of versatile network. This helps clarify trade-offs and widens the Overton Window for bus network configurations we should be considering.

What are some of these options? You could put them on a continuum from 'bespoke' ('tailor-made' - aimed at niche markets but overall low usage) to 'versatile' (aimed at doing a lot of trips well and well used). This is attempted below for Australia's largest capitals (*).

We're most interested in the 'big city' versatile network end as this is what we need to move our network towards. That is making it more useful for more trips.

Squaresville's grid is only one possibility. That's best for a dispersed, weak centred city without much of a rail network (as common in the US). Trips over the entire region are possible with just one change with many interchange points in the suburbs for local trips. How well they work depend on road intersection design; six lane roads with slip lanes and wide turning radii are common and less amenable to bus stops right at junctions that a grid network needs. A downside of grids is they require more people to change for CBD travel.

A web-style network is another option. That's better where there's a strong CBD and a substantial radial rail or busway network supported by circumferential feeders. The bringing together of lines near the centre at the web network supports higher density in the inner ring, whereas the grid network does not. And it favours the CBD which is typically the most transit-oriented part of the city. Nevertheless a web network (especially with a strong rail backbone) is efficient and still caters for cross-suburban travel if its circumferential routes are dense, frequent and connect well to the radial network. Melbourne made a major step towards rolling out a coarse web style network when it introduced SmartBus orbitals about ten years ago.

Grid and web networks are not either/or. Both can coexist in the one city. Eg Melbourne's network looks more like a web when you zoom out. Whereas if you zoom in to certain areas like the inner north, inner east and inner south-east it can look more like a grid.

A modified grid network

Do versatile alternatives to web and grid exist? If a web is best for CBD travel (but permits intersuburban travel) while a grid is good for intersuburban travel (but permits CBD travel) then which is best for travel to centres like Northland, Box Hill or Chadstone? Or the suburban National Employment and Innovation Clusters the government wants to build up? (eg Monash, La Trobe, Sunshine, etc)

The answer is neither. At least in their purest sense.

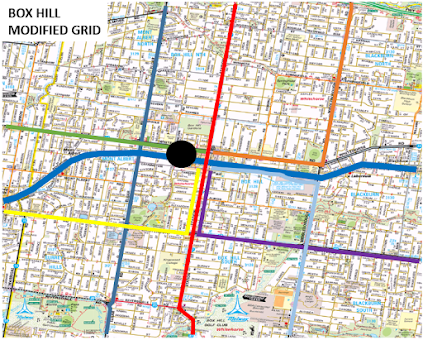

Take the hypothetical pure grid network below. Box Hill is a large centre but there are only direct connections to the north-south and east-west. Anyone coming from another direction, even if quite close by, will need to change. If they do then the few routes that go directly to Box Hill will get seriously crowded since they are carrying not only their own passengers but those who have been forced to change from other routes. On the other hand pure grid network is excellent for trips from Blackburn North to Blackburn South or if you insist on using Laburnum station (all on the orange route).

The modified grid below represents a departure from the pure grid's 'all places are equal' approach. It is assumed that Box Hill's importance justifies a gravitational pull that sucks routes in. Hence Blackburn North and Blackburn South people get a direct bus to Box Hill as their routes are bent westward there. As do those on Canterbury Rd (yellow and purple routes). Blackburn North to Blackburn South travel is less convenient but neither are likely to feature on each other's list of top destinations. And even if they did there are less likely to be parking issues than at Box Hill where public transport is likely to be more competitive (provided a supportive network exists like the modified grid below). Hence the modified grid network is better for trips that public transport is strong at (eg to major centres) at some expense to trips where it is weak at.

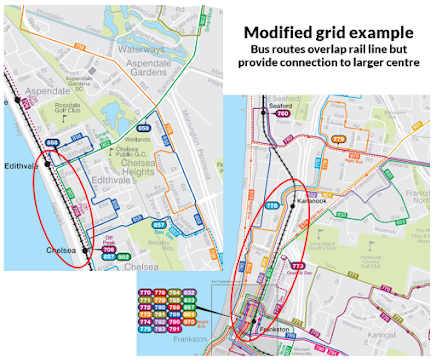

As in the Box Hill case the 901 and 902 depart slightly from the pure grid plan with some overlap along the railway. However this overlap reduces the number of short distance transfers, making travel more attractive. Plus it support land use objectives like having some increased residential densities in areas 500 to 1000m from a suburban centre.

My judgement then is that minor overlaps are probably worth the increase in service kilometres, particularly if near larger centres. In these cases attempts should be made to provide bus priority to ensure faster transit to and through them, especially where the centres are large enough to support several stops and there are passengers from the south travelling to the north side of the centre (and vice versa). A further gain is that layover time can be reduced by providing through rather than terminating services. The orbital SmartBuses do this on their intermediate stops.

The Useful Network approach

Like Squaresville, the Useful Network approach has a bias towards improved service on main corridors. However it has four key differences, as follows:

1. Useful Network respects key suburban centres with better service. It sees nothing wrong with giving Northland, Box Hill or Monash University more frequent routes from more directions than Laburnum or Jordanville. Even if it distorts the grid somewhat.

2. Useful Network supports the role of local fixed routes operating at lower frequencies in between the main roads where needed to provide a coverage function. That is a two tier network similar to that which operates in parts of Brimbank and Wyndham.

3. Useful Network routes are frequency harmonised with trains. This is considered essential with current train frequencies, particularly off-peak. Routes are normally either every 10 or every 20 minutes. While there are many more 20 than 10 minute routes the busier ones can be upgraded as patronage and resources permit.

4. Useful Network is more evolutionary in that it often starts with the existing network. This makes it less a 'blank sheet' exercise than Squaresville. It can also be done in stages, involving a few routes at a time. That may make implementation politically easier.

Click here to see what a revised Melbourne-wide Useful Network might look like

(Interactive map merges all Useful Network upgrades presented to date)

Conclusion

RMIT's 'Squaresville' paper does not constitute a practical bus network for Melbourne. Actual costs may be higher than suggested due to the need to increase frequencies on busier routes and ensure coverage inside the mile squares. Nevertheless it is extremely useful in giving some sense as to what bus reform could achieve, if only in theory. And its advocated shift towards a more versatile network throughout Melbourne is essential.

The question remaining then is the best way it can be made into a practical, useful and generally acceptable network in real life. My bet is some sort of two-tier network that preserves local coverage while simplifying main road routes, boosting access to key suburban destinations and connecting well with trains. Squaresville is thus an inspiration not a blueprint.

(*) Notes on network development. Brisbane and Adelaide have the least developed networks due to a lack of routes to anywhere but the CBD. Both have poor train frequencies on most lines, not helped by buses that duplicate rather than feed trains. All frequent buses are on radial routes.

Perth and Melbourne both have strong radial routes with Perth's trains being more frequent but Melbourne having more lines. Both also have strong circumferential bus routes with Perth's being better coordinated with trains but fewer in number. However both cities have limited services on many local area routes.

Sydney is the stand-out with a less radial rail system operating at good frequencies 7 days. There are also some outer suburban busways and a significant number of frequent bus routes. Its streets are less grid-like so its network is more like a somewhat broken web.

PS: An index to all Useful Networks is here.

3 comments:

An outstanding analysis. One of the most useful contributions to the Melbourne transport discussion I’vs seen in a long time.

They have been far too ready to remove bus routes from streets halfway in between the routes they propose, even when they have decent patronage generators like station, shopping strips, shopping centres, etc. Nothing on important and well patronised local routes like those along Poath Rd, Koornang Rd or MacKinnon Rd.

The excessive short transfer trips to major destinations does not just apply to the railways, but also with bus routes. The biggest example of this is probably Chadstone, which goes down to only their Dandenong Rd route for all patronage (not even their Warrigal Rd bus goes vis Chadstone). Hopelessly inadequate

Thanks for reading the paper!

Walking and waiting times

Could I clarify this, to ensure no misunderstanding by your readers. Walking costs to and from stops, and between stops on transfers, were all included in the calculated travel times.

Walking time was calculated as if walked at 5 km/h. Where bus stops were further from stations, or on main roads outside Monash Uni or Chadstone, the extra walking time was included in the calculation, whether at the start or end of the trip or on a transfer.

Waiting costs were calculated as half the time between services. So a trip on two buses, each with a 15 minute service interval, was calculated with 2 x 7.5 minute waits.

The quoted sentence just meant that no additional intangible time penalty (say, 10 extra minutes per transfer) was added over and above the walking and waiting time involved in the transfer.

The modelled routes don't necessarily add more transfers to all trips. Some trips would become possible on two intersecting bus routes, whereas at present they require a bus to a train, plus train trip, plus another bus at the other end. In real life, the intangible time penalty users assess for these trips mean they probably get made by car.

Outer suburbs – compared to what we now have

I do think people in some outer suburbs currently get a rough deal. If you live in Clyde North, you have a bus to your primary activity centre in Cranbourne. But getting to a second centre in Berwick (schools, sports facilities, hospital, shops) probably involves bus to Cranbourne + train to Dandenong + train to Berwick. Rather than a direct bus straight up Berwick-Cranbourne Rd.

We should be explicit about the choices we make. It's great that some suburbs currently have a grid of intersecting north-south and east-west routes spaced 800m apart. Do we:

(1) spend more so those suburbs can keep their 800m grid, and Clyde North gets a 1600m grid, or

(2) reallocate resources so both have a 1600m grid, or

(3) come up with an explanation for why it's fair for some suburbs keep their 800m grid while others get none.

Modifying the grid – Blackburn

Your discussion of Blackburn (where I happen to live) is thought-provoking. There is enough car traffic between North and South Blackburn to justify the level crossing removals that have occurred at both Middleborough and Blackburn Rds, but no bus crosses the rail line on either road.

For passengers using the bus to get to a station, bending routes to Box Hill serves little purpose. It makes little difference whether they board a city-bound train at Blackburn, Laburnum or Box Hill.

For shopping, there's an element of picking winners. Perhaps we shouldn't pick a shopping destination for people in Blackburn North by bending their bus routes to Box Hill, rather than straight down Blackburn Rd to Kmart Plaza at Burwood Hwy (and on to Monash University). Or, for Middleborough Rd, to the new Burwood Brickworks shopping centre (and on to, say, Monash Medical Centre).

Having most routes end at railway stations (rather than pausing at the station, then continuing on in the same direction over the line) makes the rail line a barrier. We could enhance local engagement if we had routes that established connectivity across communities divided by a main road or railway line.

Post a Comment