A stealthy theft of time and space is making driving faster and walking slower in suburbs across Melbourne. Individual small changes spread across hundreds of sites is creating a tsunami of slowness driven by state and council authorities who in words claim to support 'active transport'.

Decisions, made by faceless technocrats in road authorities, happen without public accountability or oversight. Yet they're changing the way that we get around, prioritising driving over walking and public transport, even for very local trips. Whether intended or not, the effect is induced car traffic and stronger business cases for more and wider roads. That repeats the vicious cycle as walking becomes even less attractive across increasingly severed communities.

This theft has been happening for 60 or 70 years. Newer suburbs have known nothing else. Older suburbs got it imposed on them. And it's still going on. Including under the cover of apparently connectivity improving projects such as level crossing removals. In some cases old direct walking paths got obliterated as crossing removals merely substituted one type of barrier for another. In other instances added turning lanes widened roads and thus reduced connectivity for walkers crossing. Certain works, such as less direct paths and replacing zebra crossings with lights, is a walking time grab that just induces more driving despite being done under the guise of accessibility and safety.

Space taken

As mentioned before, this theft can involve space, time or both.

An example of a space theft is where a road is widened. Instead of having to cross four lanes a walker may have to cross six or eight lanes. This is harder and scarier, especially for the less mobile. Particularly at unsignalised points, which is most places. The recent Getting to the Bus Stop study by Victoria Walks found that 60% of bus stops were on high speed roads. Of those fully 95% lacked a pedestrian crossing within 20 metres.

Widening projects that incorporate roundabouts or slip lanes are even worse, especially where there are no zebra crossings on the approaches. As well as taking more space the geometry works against bus-bus transferring passengers as stops are pushed back from the intersection. Because reaching a stop requires multi-road crossings, multiple long waits at lights and long walks, this greatly reduces connectivity to and between bus routes. The diagram below paints the picture. Or you can tour a real example involving intersecting SmartBus routes at Springvale Rd/Wellington Rd here.

Signals were proposed due to a high number of crashes (even back then they used the misnomer 'accident'). They could be synchronised (timed) or vehicle actuated with the latter suggested for Point Nepean Rd near Martin St (amongst other locations). The 1940 article says that the real danger spots (for motorists) were at 'busy but not obviously busy' intersections. Somewhere like Camberwell Junction was 'so obviously busy' that it engenders care do was less dangerous. Even then they knew stuff that is starting to be 'rediscovered'.

Nepean Hwy near Martin St got their lights in 1939. A reason given for their existence was to allow pedestrians to cross despite heavy traffic, especially on weekends and race days.

The lights ran on fixed cycles of 45 seconds total. Martin St got 11 seconds (green) with 4 seconds amber while the busier Pt Nepean Rd got 26 seconds (green) with 4 seconds amber. In the worst case scenario if you just missed a green on Martin St you would wait 34 seconds before your time comes around. Remember those times, noting that the then Point Nepean Rd was one of Melbourne's busiest.

There were several different styles of traffic signal in these early years. One style was developed by Charles Marshall who was concerned that existing signals did not give warning that they were going to change. His signals did with two dials at 90 degrees facing oncoming traffic on each road. These showed how long you needed to wait and how long you had. Like today's lights Marshallites had red, amber and green aspects. Some background on the Marshalites is here.

In 1947 Charles Marshall offered to install his lights much further down Point Nepean Rd near Main St and Tyabb Rd (Mornington). Councillors expressed varying views on their desirability. Cr Bradford was concerned about 'heavy traffic that would be stopped every 40 seconds'. Cr Nunn said that it 'was a heartache for a mother to send her children to school' (at a time when most walked independently) and that (traffic) 'having to stop for a short time' should not be a worry. Cr Fielding agreed, saying that 'the motorist, instead of learning manners, was now worse than ever before'.

Look at the seconds elapsed as the hands move to where they start. You'll notice that the total cycle time is 45 seconds. The red and green areas are roughly equal, meaning that each direction gets about the same amount of time.

A disused Marshalite signals sits in Chelsea's Bicentennial Park. While not currently operational they were restored so that they were when they were first moved there. The walk phase and its associated amber is about one-third the total cycle time.

The Martin St Brighton lights mentioned before were apparently not Marshalites. However as you saw from the article they had a 45 second cycle time. As did the Marshalites you read about and saw demonstrated. Thus it's fair to conclude that 45 seconds was not an unusual cycle time for traffic signals, even those on major roads.

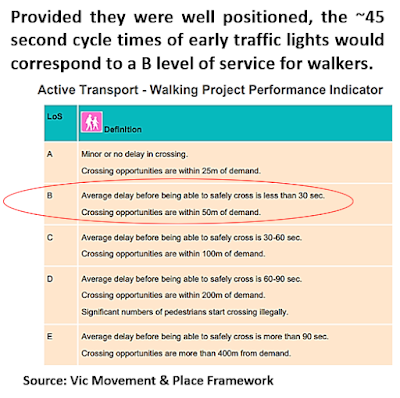

While not perfect for dense walkable areas, a 45 second cycle time still stacks up quite well (a B level of service) for walking connectivity when viewed from the perspective of the Department of Transport's Movement and Place Framework for active transport. Lights with short cycles have far fewer people crossing against them than where cycles are longer.

How long does it take today?

Basic walking needs have not changed much in decades. What was poor for a traffic signal 80 years ago will still be poor today. This likely extends to matters like willingness to wait and risk-taking behaviour. What has changed has been the roads and the traffic signals. Below is a video case study from the intersection of Nepean Hwy and Martin Street in Gardenvale.

This is not an isolated case. Projects other than road widenings, such as level crossing removals, can also increase walking times. This is especially if they foist current traffic engineering practice onto century old communities designed and built around trains and walking.

You only need to go a bit further down Nepean Highway to find an example. Chelsea recently got its level crossings removed. Local walking access conditions changed. Gone was the old station underpass whose exit aligned with pedestrian lights across to the shops on Nepean Hwy. This got replaced by a footbridge that, unlike the old underpass, has no pedestrian lights near its highway exit. The result is that walkers from the bus or nearby streets have a less direct, unsheltered and unshaded walk before they reach inconveniently placed lights and often have to backtrack to their destination.

This poor outcome is a direct result of LXRP-associated engineers ignoring walking as an important local transport mode and its need for good permeability at multiple points. See the consequences for yourself in "Hot, Wet & Disconnected" below.

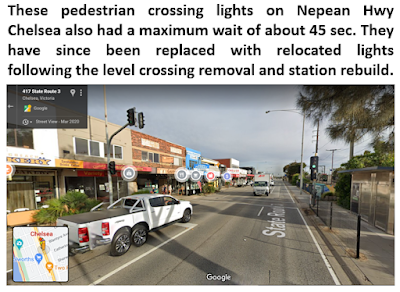

But wait, there's more! Not mentioned in the video was that pedestrian light timings have lengthened, further extending walking times. For example the (inconveniently located) southern pedestrian lights at Nepean Hwy has a maximum wait of 60 seconds versus 45 seconds on the removed crossing (conveniently near the old station's underpass).

Another highway crossing further north near The Strand has an even longer 80 second maximum wait at lights on both (busy) Nepean Hwy and (quieter) Station St. This is despite Kingston Council advocating it as a major pedestrian connection and even partly funding a footbridge. Notwithstanding their effect on walking access and safety, signal timings are considered obscure technical business rarely discussed in public.

Walking in metropolitan areas today is slower than what our grandparents (if they lived in Melbourne) would have experienced. This is due to less connected street patterns and double or triple the waiting at signalised intersections. Also, due to lower car traffic volumes, there would have been more times they could cross mid-block without waiting long. All are direct consequences of thousands of small decisions made over many years.

The Department of Transport is currently reviewing traffic light timings . However there's no transparency or word on the values that guide either it or technology like Smarter Roads. Especially for people who walk for transport in the suburbs. Something like the Movement and Place framework may list movement as a priority for a major road corridor and give car traffic free flow. However this risks downplaying the road's role as a barrier for walkers needing to cross it.

Our grandparents would have waited half the time for a tram as we do today. This is because tram frequencies have dropped (notably in the 1950s and 60s) with only a weak recovery since. The most recent news is of a cut, rather than an increase, for tram frequencies. Also in-tram travel was faster due to fewer cars on mostly shared roads being in the way. Even major train lines, like Frankston, have longer end-to-end travel time than they did in the 1990s with the trip to the city now exceeding an hour while there's new parallel freeways that weren't there then.

Maybe it's these sorts of issues that our billions allocated for 'Big Build' projects should be tacking across Melbourne. Even if some (particularly traffic inducing freeways) are cancelled with funds diverted to (say) 10 000 'Little Build' projects instead. More people in more neighbourhoods could well be better off.

1 comment:

This reminds me of the Mentone Station rebuild. The old Mentone Station had a small ramp leading to it from Como Pde and it was a short walk from Como Pde through the concourse onto the city-facing platform.

When the new station was announced I presumed that the station concourse would be on street level with a lift or stairs down to the platform, like at Bentleigh. Instead for whatever reason the concourse is well above street level and there are several flights of stairs leading up to it from the street. Now, suppose you are a wheelchair user or have walking difficulties or have a pram. In that case you have six - six! - ramps to get you from street to concourse. A massive extra walking distance and for what?

Post a Comment